Source: CoalZoom.com

August 17, 2021

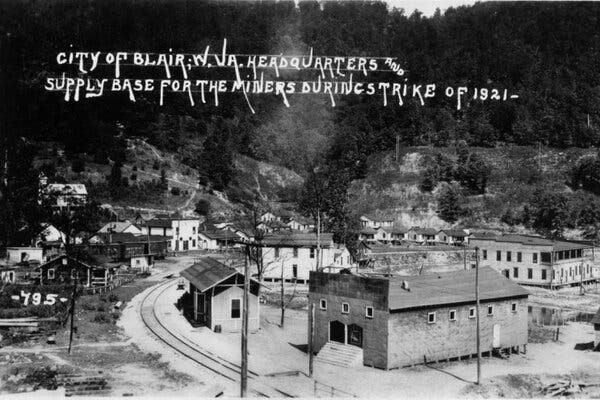

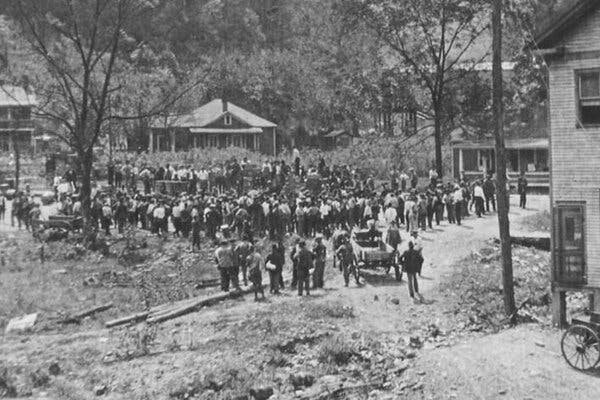

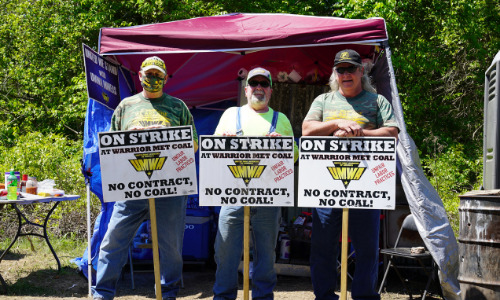

History repeated itself as hundreds of miners spilled out of buses in June and July to leaflet the Manhattan offices of asset manager BlackRock, the largest shareholder in the mining company Warrior Met Coal.

Some had traveled from the pine woods of Brookwood, Alabama, where 1,100 coal miners have been on strike against Warrior Met since April 1. Others came in solidarity from the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania and the hollows of West Virginia and Ohio.

Among them was 90-year-old retired Ohio miner Jay Kolenc, in a wheelchair at the picket line — retracing his own steps from five decades ago. It was 1974 when Kentucky miners and their supporters came to fight Wall Street in the strike behind the film Harlan County USA.

“Coal miners have always had to fight for everything they’ve ever had,” Kolenc said. “Since 1890, when we first started, nobody’s ever handed us anything. So we’re not about to lay our tools down now.”

The longest that miners ever went on strike was for 10 months in 1989 against the Pittston Coal Company in West Virginia, defending hard-won health care benefits and pension rights. Some 3,000 miners got arrested in that strike. AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka, who passed away on August 5, was president of the Mine Workers (UMWA) at the time.

In Manhattan, mixed in the sea of camouflage T-shirts outside BlackRock was a smattering of red and blue shirts — retail, grocery, stage, and telecom workers. The miners and supporters circled the inner perimeter of four police barricades, chanting “Warrior Met Coal ain’t got no soul!” and whooping it up.

Postal and sanitation trucks honked in solidarity. “You’re in New York City,” Mine Workers President Cecil Roberts told the crowd. “When somebody comes by driving a trash truck, they’re in a union. Chances are, somebody comes along with a broom in their hand, they’re in a union.”

“Where’s Our Money?”

The strikers are fighting to reverse concessions that were foisted on them in 2016 when newly formed Warrior Met Coal bought two mines and one preparation plant from Jim Walter Resources during bankruptcy proceedings. BlackRock became one of the three majority shareholders in the new company.

Since then, the union calculates that workers have forked over $1.1 billion in pay, overtime, vacation, safety, health care, and other benefits to help the company regain solvency. Today 26 hedge funds have investments in Warrior Met stock, signaling their confidence in its profitability.

“We want everything back. And then some. That’s the message we’re trying to send to BlackRock,” said Michael Wright, a miner for 16 years.

Warrior Met produces coal used in steel production in Asia, Europe, and South America. In response to the strike it has scaled back production, left one mine idle, and stopped stock buybacks, Bloomberg reported. The strike has cost the company $17.9 million, according to its second-quarter earnings report.

Shortly after the miners walked out, management returned to the table with an offer that would have recouped just $1.50 of the $6 cut in wages from the 2016 contract and left intact punitive disciplinary policies and benefits concessions. The miners voted it down, 1,006 to 45.

“We come back to the table and they’re offering less what we were making originally,” said Brian Seabolt, another 16-year coal miner.

“We go underground to sacrifice our lives for our families,” said Wright. “They’re making billions of dollars. Where’s our money?”

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink has burnished his public image as a benevolent capitalist concerned about climate change and social justice. The strikers hope to gain leverage by tarnishing that image.

BlackRock has a shield that makes that harder: two-thirds of its investments are in index funds, passively managed portfolios that bundle together investments regardless of social impact.

But it’s even harder to hit it hard enough in the pocketbook to have an impact: Warrior Met makes up just a tiny fraction of BlackRock’s portfolio. The asset manager had a record $9.5 trillion in assets under management at the end of June.

Nonetheless, to hurt profits, strikers were blocking scabs from entering the mines — until the company obtained an injunction to stop them. Despite that, the mines produced only 1.2 million tons of coal during the second quarter — a million less than the same period last year.

A Grueling Job

Another striker on the Manhattan picket line was Tammy Owens, a former steelworker. She switched to mining because it had better pay and benefits, though the job was grueling. “And then a few years later, I ended up with worse benefits than what I had at the steel plant,” she said.

Since the strike, she has picked up a side job to provide for her family. The union has also distributed $4.3 million to miners to cover health care.

Besides pay and benefits, the 2016 concessions included a punitive attendance policy that one miner’s wife described to journalist Kim Kelly as “four strikes and you’re out.”

“If I had a heart attack, they can give me a strike,” Owens said. “They don’t accept a doctor’s excuse. Even if I have something contagious that I can give to other people — pneumonia, the flu, strep throat, you name it — you have to come to work.”

Excessive overtime is another flashpoint (shades of Frito-Lay and Amazon). Miners have been forced into 12-hour shifts stretching into weekends — without the double pay on Saturday and triple pay on Sunday that they used to get.

And health care looms large. Costs shot up; the company now covers only 80 percent of the premium. “We need 100 percent,” said miner Dedrick Gardner. “Considering the work conditions in a coal mine, health care is vital. You’re dealing with silicosis, black lung, diesel, smoke.”

Black lung is caused by breathing in coal dust. The dust silts up the lungs, scarring and destroying them.

“Health insurance went from $12 for seeing any doctor in the world to $1,500 family deductible and co-pays up to $250,” said Local 2245 President Brian Michael Kelly.

Toxic and Dangerous

Safety is a perennial concern. “I work 2,200 feet underground in one of the most gaseous mines in the world,” Owens said. “If something goes wrong, it could blow the top off the ground.”

In 2001, 13 workers died at one of the mines now owned by Warrior Met after a slab of rock fell and set off a methane gas explosion, burning and pounding miners to death with chunks of rock.

Despite that tragedy, the 2016 contract eroded safety standards. And the situation is presumably even worse for the scabs inside now.

“Nonunion mines are continuously known for cutting corners and creating unsafe working environments in order to increase production,” said union spokesperson Erin E. Bates via email. “Warrior Met Coal is currently mining and processing coal with unskilled workers. We are concerned it is only a matter of time until someone gets seriously hurt.”

Without the union watchdog, apparently the company’s environmental practices slipped too. Shortly after the strike began, wastewater from one of the mines suddenly turned local creeks black with pollution.

Written by: Luis Feliz Leon