On March 8, 1924, a series of explosions occurred at the Castle Gate coal mine in Carbon County, Utah. The first blast was attributed to inadequate watering down of the coal dust from the previous shift’s operations. A fire boss was investigating methane gas near the roof of the mine when his lamp went out. He attempted to relight the lamp with a match which ignited gas and coal dust, setting off a chain reaction of explosions in the mine, killing 172 miners. The disaster left 110 widows with 264 children. There were no survivors.

The force of the explosion was so powerful it launched a mining car, telephone pole, and other equipment nearly a mile from the entrance of the mine. “Safety laws were all but nonexistent when this horrible explosion occurred a century ago,” said President Roberts.

“After the disaster, the government reviewed safety laws and created amendments and resolutions to make mines safer. This included funding for mine inspectors, requiring coal dust to be cleaned from abandoned rooms, and many others. These new procedures by no means stopped other mining disasters, but they did help improve the safety of the mines,” Roberts said.

“Castle Gate is the second worst mining disaster in Utah’s history,” said International District 22 Vice President Mike Dalpiaz. “The United Mine Workers started organizing in Utah around 1933 and this tragedy helped the union in that effort because miners wanted safety laws enacted.”

“The nationalities of the men killed in the explosion were Greek, Italian, English, Welsh, Japanese and Austrian. Ironically, our union was established by immigrants from all over the world who wanted to form a union, and that’s what the UMWA did in the years following this terrible tragedy; a tragedy that did not have to happen,” Dalpiaz said.

Relief Fund for the Victim’s Families

Immediately following the aftermath of the explosion, the Red Cross arrived at the scene to help the victims’ families. The governor at the time, Charles R. Mabey, realizing the community would need additional relief, called for public subscription to a relief fund for widows and children. He formed a committee to distribute $132,445.13 that was collected for the aid of the 417 individuals who were left without support following the disaster.

The committee hired a social worker to assess needs and disburse funds. The families did not receive disbursements from the fund for over three months after the disaster because it took time to gather the money from various banks across the state. The fund expired in December 1935, and the committee held its last meeting on January 12, 1936.

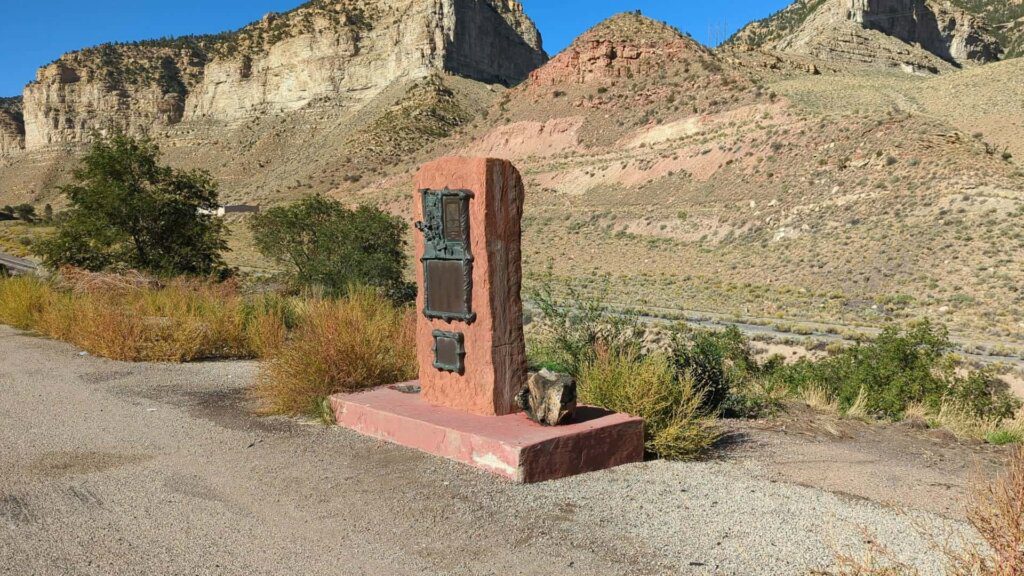

Today, a granite and bronze monument is located in the canyon north of Helper to mark the general location of the explosion. The Castle Gate cemetery, which contains many of the victim’s graves, sits east of the canyon.