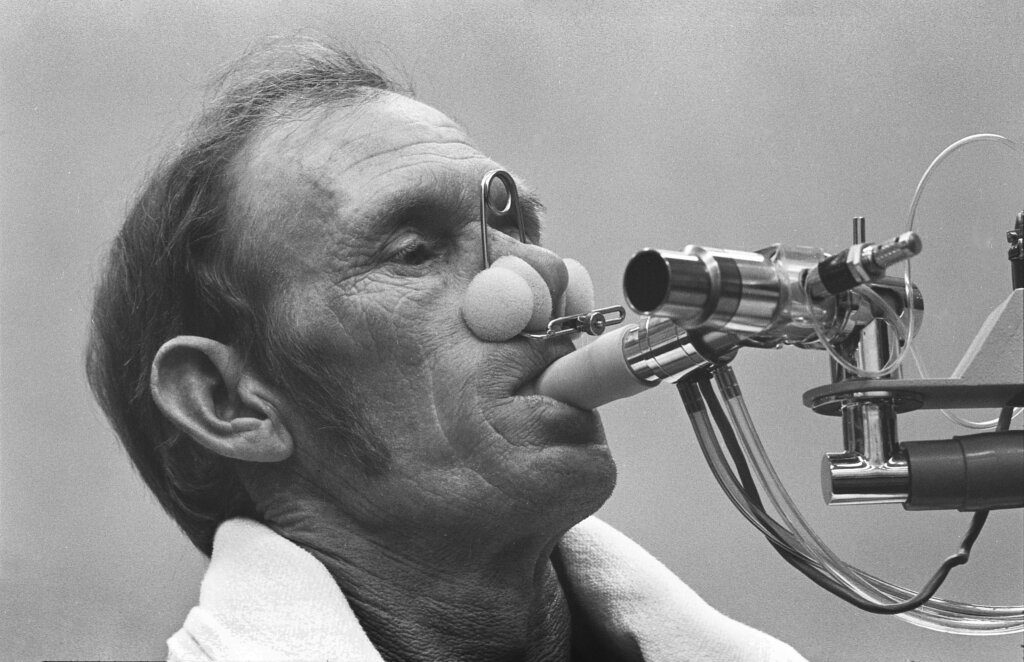

The resurgence of coal miners suffering from Pneumoconiosis or Black Lung disease in the last several years, and significantly in younger miners, are subjecting them to a shortened and debilitating existence. The disease destroys the body and leaves many to die a suffocating death. For decades, many denied that the condition even existed even though there are thousands of recorded deaths of the horrific disease.

Miners and advocates have been lobbying and rallying the 1960s for laws and regulations regarding Black Lung. In the 60s, women were at the forefront of the fight as many of them were left to watch their husbands suffer for years from the disease and in most cases, die. In the 70s, miners from across the United States came to rally in Washington, DC to support the nation’s first federal Black Lung legislation.

When the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969 passed, it provided for monthly benefit payments to coal miners who were completely disabled as a result of Black Lung, to the widows of coal miners who died as a result of the disease and to their dependents. Several amendments have been made to the Act in the 70s, early 80s and as recently as 2010.

In 2018, data from Black Lung clinics across Appalachia and studies by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) revealed the unprecedented reoccurrence of Black Lung in younger, less experienced miners who had contracted the disease at a significantly earlier age than the generation of miners before them.

Research and Findings of Silica Exposure

NIOSH, along with researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago looked at the records of 235,500 deceased miners and described it as “the largest study of its kind to date.” The study found that mortality had worsened over time with modern miners facing greater risk than their predecessors. It also found that miners in the Central Appalachian areas of eastern Kentucky, southwest Virginia and southern West Virginia faced the most severe risk.

The study found that ‘progressive massive fibrosis’, which is only caused by dust inhalation, was also more frequent in younger age groups and it appeared likely that coal mine dust inhalation also contributed to their increased burden of nonmalignant respiratory disease.

In 2022, it was reported by Dr. Robert Cohen of the University of Illinois-Chicago that exposure to toxic rock dust appears to be “the main driving force” behind the recent study of severe Black Lung disease among coal miners. The study examined the lungs of modern miners compared to miners who worked decades ago. This provided the first evidence of its kind that silica dust was responsible for the rising tide of advanced disease, including miners in Appalachia.

“This is the smoking gun,” Dr. Cohen said. Up to now, there has been indirect evidence of the link, but this study went further, testing lung tissues for the concentration of silica particles. “It turns out we were right. The pattern of pathology was very, very consistent with silica,” said Cohen.

Cohen’s study specifically looked at contemporary miners with severe disease and what was lodged in their lungs compared to older workers who also had severe Black Lung disease. Among their findings was that the more contemporary workers (born after 1930) had more silica in their lungs than the miners who were born between 1910 and 1930. Cohen urged the federal government to toughen Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) regulations on silica dust in mines.

The University of Illinois Chicago/NIOSH study additionally found coal miners, particularly those exposed to silica dust, had significantly increased odds of dying of lung cancer compared with the general U.S. population.

“The study proves what we have been saying for years,” said President Roberts. “Today’s miners are contracting lung diseases at an alarming rate.

“I testified before Congress in 2019 on this exact issue and nothing was done until now,” Roberts said. “Finally, four years later, we have a proposed rule to limit the level of silica dust in mines, meaning that miners will no longer be subject to breathing in microscopic rock particles that will never leave their lungs,” Roberts said.

“I commend all those who have been fighting so long to see this day come; most especially the miners who contracted this insidious and always-fatal disease, their spouses and their children. While they have borne the brunt of the disease, they have never lost their will to fight to see that no one else ever gets it.” —Cecil E. Roberts—

MSHA’s Proposed Silica Standard

On June 30, the U.S. Department of Labor announced a proposal by MSHA to amend current federal standards to better protect the nation’s miners from health hazards related to exposure to respirable crystalline silica (silica dust). The proposed rule change will ensure miners have at least the same level of protections as workers in other industries.

“Workers in other industries have long been protected from excessive exposure to silica dust, but miners were not. Finally, the government is taking steps to protect our nation’s miners,” said Secretary-Treasurer Sanson.

Assistant Secretary for Mine Safety and Health Chris Williamson said the purpose of the rule was simple; prevent miners from suffering from debilitating and deadly occupational illnesses by reducing their exposure to silica dust.

The proposed rule would require mine operators to maintain miners’ Permissible Exposure Limit to respirable crystalline silica at or below 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air for a full shift exposure, calculated as an 8-hour time weighted average. If a miner’s exposure exceeds the limit, the proposed rule would require operators to take immediate corrective actions to come into compliance.

“While the UMWA commends MSHA for this proposed ruling, there is still more work to be done,” said Sanson. “This is only the first step of many more that will be required. We must get this rule finalized as soon as possible, and we also need to ensure that mine operators follow the rule and the government enforces it.”

- MSHA’s proposed respirable crystalline silica rule would apply to coal mines and all metal and nonmetal mines

- The proposed rule would impose significant administrative and technical requirements on operators and lacks Table 1 type of porvisions that would help operators maintain compliance while providing for appropriate protections of miners

- The final rule would become effective 120 days after its publication in the Federal Registrar