Date: 9/24/2023

Author: JUSTIN VELLUCCI

Photos: SHANE DUNLAP

Tribune-Review

Mark Rankin left the coal mines, but the coal mines haven’t left Mark Rankin.

Stocky and broad shouldered, the retired Uniontown-area coal miner trekked to a Washington County health clinic to see if recent coughing and tightness in his chest could be black lung. Rankin worked for years stripping coal in Soberdash Coal Yard near Connellsville, Fayette County.

Sporting denim, a shiny belt buckle bearing an M, and cowboy boots, Rankin spoke in clipped sentences at Lungs at Work, a black lung clinic in Peters Township — the closest one to Pittsburgh. He punctuated occasional words with a slight drawl.

“I’ve had (breathing problems) before, but I never paid attention to it,” said Rankin, 73, of Haydentown, a postage stamp-sized community in Fayette County. “I always thought that if something’s not bothering you too much, don’t bother it.”

Black lung is debilitating coal miners at its highest rates in 50 years. Formally called coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, black lung occurs when miners inhale coal dust. Over time, continued exposure to coal dust scars the lungs, impairing the ability to breathe, according to the American Lung Association.

The federal government and advocacy groups are stepping up efforts to combat the resurgence.

The Mine Safety and Health Administration, an agency of the federal Department of Labor, plans to enact a proposal restricting how much silica dust a miner can breathe during a shift.

Because coal seams are smaller than in previous decades, miners now must cut through more rock, MSHA said. Prolonged exposure to silica — the sometimes white, sometimes pink dust produced when cutting rock such as quartz — may cause black lung, other lung diseases and cancer, medical experts said.

A comment period closed Sept. 11 on the proposal, which MSHA hopes will stem the black lung spike. Officials expect to implement the new standard after announcing a timeline this fall.

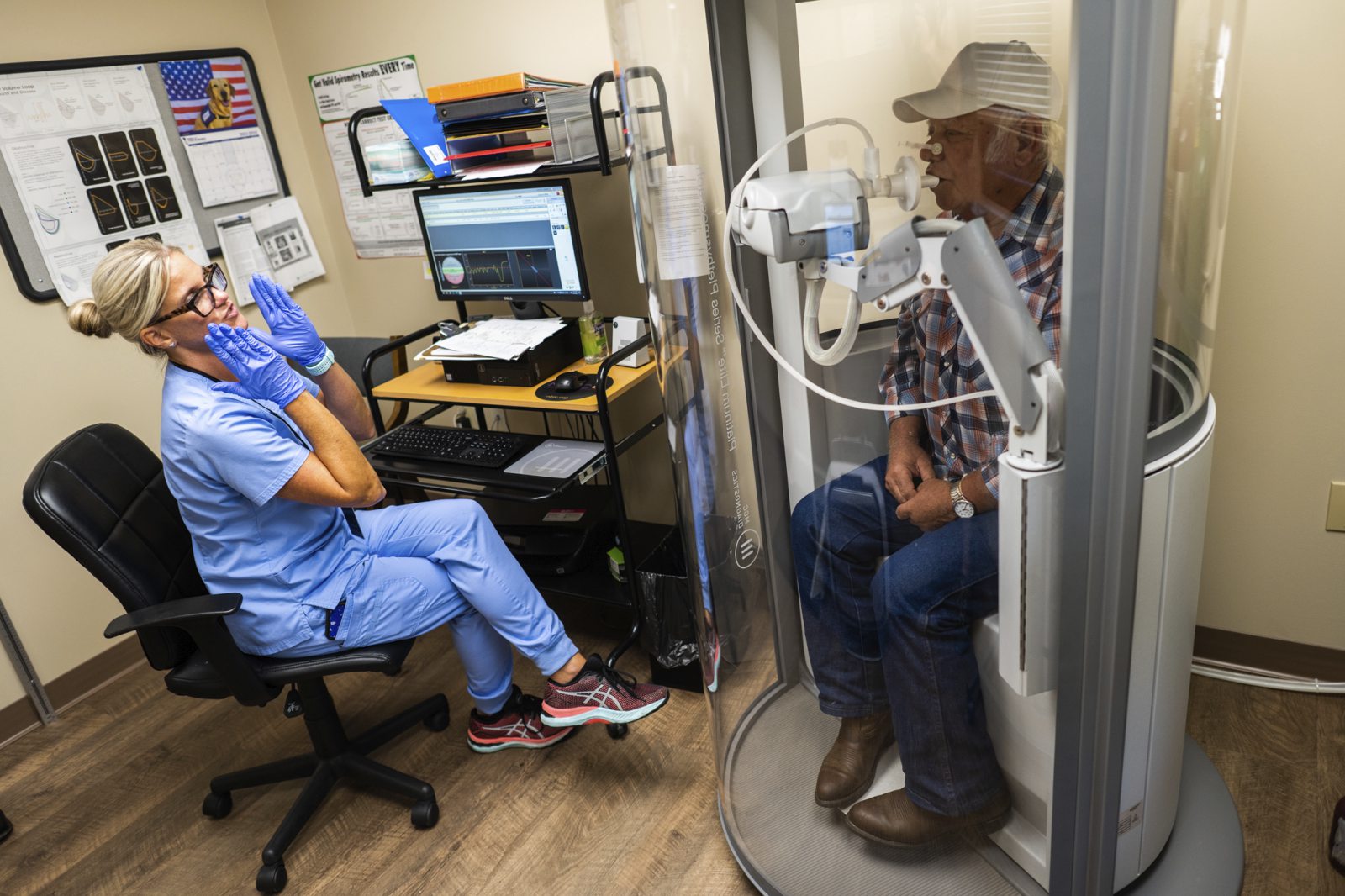

In late August, Rankin sat in a 6-foot-tall plethysmograph cylinder at the Lungs at Work clinic, clamped his nose shut and prepared to test his breathing.

“Normal breathing, OK?” patient care coordinator Joanna Szalay told him.

“Now, go!”

Rankin puffed furiously into a mouthpiece.

“In and out! Faster, faster!” Szalay blared. “Take a deep breath in, now push it out! You keep blowing, you keep pushing!”

After a few takes, Rankin was exhausted. He put his hand to his chest.

“I can feel that right there now. I can feel that it’s tightened up since I started,” Rankin said. “But I never let that stop me. I always look at it this way: ain’t nothing easy, not about anything.”

Now he waits.

The clinic said, even if the tests indicate black lung, it will take Rankin 18 months or longer for the federal government to decide whether he’s eligible for black lung benefits.

Black lung resurgence

Rates of black lung have more than doubled in the past 15 years, and incidence of the disease’s most severe form are at the highest levels in more than a generation, according to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health.

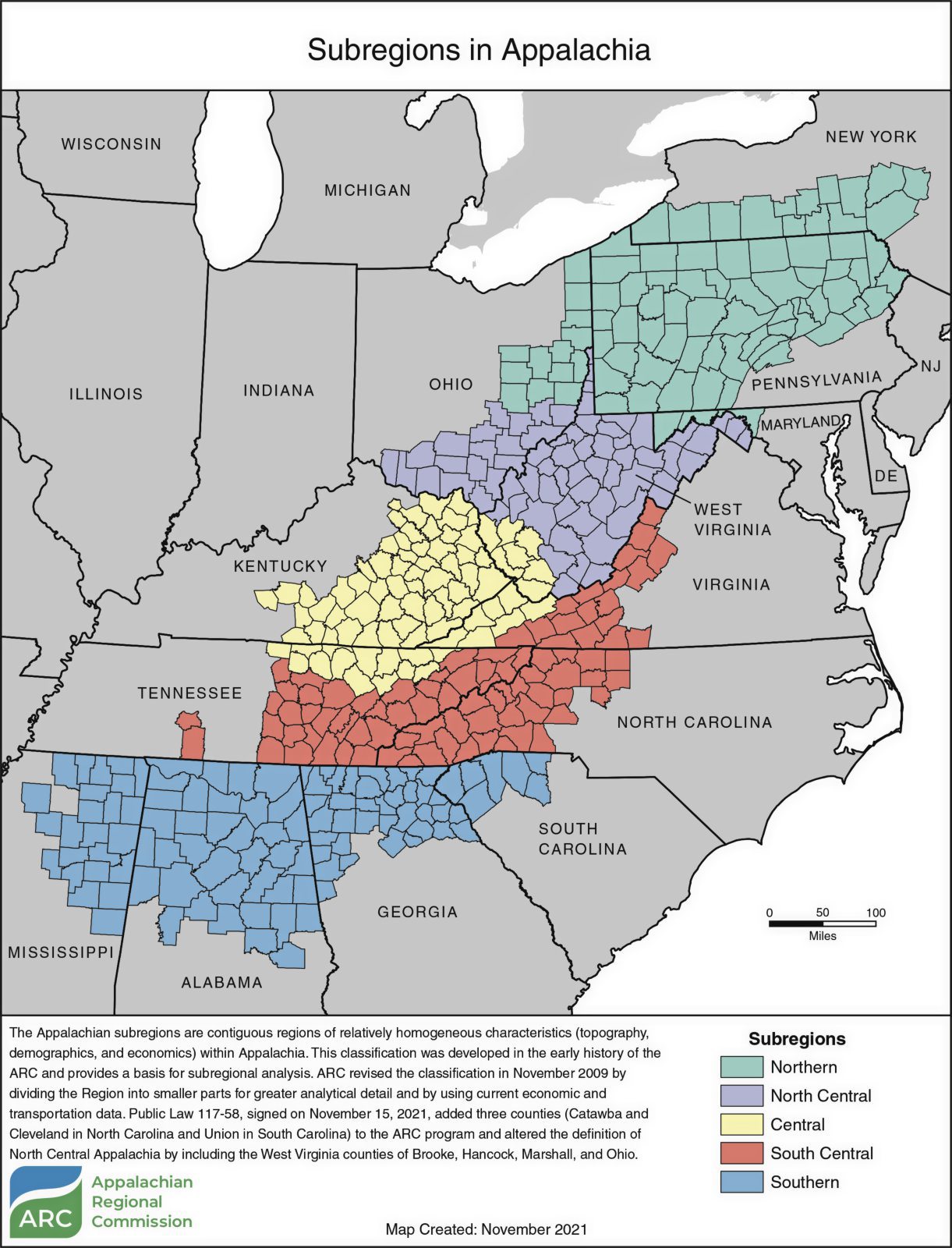

Today, 1 in 5 veteran coal miners in central Appalachia will be diagnosed with black lung, officials said.

Pennsylvania, which sits in what is called northern Appalachia, is rich in coal history.

In 2021, the state was the nation’s third-largest coal producer, behind Wyoming and West Virginia, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. There are more than 2,100 mines in Pennsylvania employing more than 11,000 people, the DEP and MSHA said.

Allegheny County has only seven active mines — none in the City of Pittsburgh — but there are 18 in Westmoreland County, 32 in Greene County and 39 in Butler County, the state Department of Environmental Protection said. Lawrence County tops the regional list with 50 active mines.

The region also is home to the largest underground coal mine complex in North America: the Pennsylvania Mining Complex, located in Greene and Washington counties. The Consol Energy-owned facility produces about 28.5 million tons of coal each year — more than half the coal Pennsylvania produced in 2022, the U.S. Energy Information Administration said.

Consol Energy, a coal producer based in Canonsburg, Washington County, and others with mining interests in Pennsylvania and northern West Virginia did not return calls or emails seeking comment for this story.

There also are mine operations in Armstrong County, which sits just outside what the U.S. Census Bureau calls the Pittsburgh Metropolitan Statistical Area. Last year, the DEP granted Rosebud Mining, a Kittanning-based company that operates several local mines, a permit for a new, 280-acre surface mine in Cambria and Somerset counties.

Black lung kills 1 of every 3 miners

Black lung has no cure. And it kills.

The progressive disease kills about 1,000 miners a year — and more than 76,000 in the past 50 years, according to MSHA. That’s almost one-third of the 235,000 U.S. coal miners who died between 1979 and 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said.

Progressive massive fibrosis, or PMF, is the most severe form of black lung. Coal miners reported about 4,700 PMF cases to the federal government between 1970 and 2016, a 2018 study in Annals of the American Thoracic Society found.

PMF cases among black lung benefits claimants fell from 404 in 1978 to a low of 18 cases in 1988, the study found. But that number shot up to 353 cases by 2014.

A total of 67 PMF cases were reported at Pennsylvania clinics from 2019 to 2023, according to the University of Illinois Black Lung Data and Resource Center.

The center could not provide the total number of Pennsylvania miners killed by black lung. Neither could MSHA.

In addition to Lungs at Work, there’s a second Washington County black lung clinic in Fredericktown. UPMC, which declined comment for this story, operates another in Altoona.

The new MSHA rule — which applies to all miners, not just those mining coal — aligns the industry with 2016 Occupational Health and Safety Administration guidelines, said MSHA Assistant Secretary Christopher Williamson.

Coal accounts for just 20% of operating mines nationwide; the rest mine metals and nonmetals.

“It affords all miners the same level of protection other workers have,” Williamson said. “We know silica is a toxic substance, and we know what the health effects of it are. … That’s what we’re trying to prevent with this proposed rule.”

Feds take heed

Government officials are paying attention.

In 1969, Congress enacted the Federal Coal Mine Health and Safety Act to establish black lung benefits. In 1972 came the Black Lung Benefits Act, which started monthly payments to miners with black lung.

Black lung cases dropped through the 1990s. By 2012, though, the rate had increased tenfold, the Center for Public Integrity reported.

In 2014, pushing back on a rising tide of black lung cases, MSHA restricted how much coal dust a miner could breathe during each shift. The new rule on silica was under review even before the 2014 coal-dust restrictions, MSHA said.

U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, D-Scranton, and other elected leaders have advocated to update miner health laws. Last year, President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which continues to secure federal black lung benefits for sickened miners.

Coal miners, unions, industry groups and elected leaders told the Tribune-Review they support the new silica dust rule.

“The safety and health of our nation’s miners is the primary concern of all our members,” said Ashley Burke of National Mining Association, a 250-member industry group. “Over the last two decades, effective ventilation controls, implementation of industry best practices, strict adherence to mine ventilation control plans, increased operator and miner safety awareness, and the 2014 dust rule have all contributed to exponentially lower dust levels inside the mine.”

Casey called the proposal “a step in the right direction.”

“Coal miners have moved our nation forward for generations, risking their lives and their long-term health to power our factories and heat our homes,” Casey told the Trib. “We also have an obligation to miners suffering from black lung disease, as well as their families.”

This year, Casey pressed the Government Accountability Office to reevaluate black lung benefits. Such benefits are tied to federal pay scales and not the Consumer Price Index, which measures inflation, his office said.

Some worry those benefits haven’t kept up with inflation.

When black lung benefits started in 1969, single miners received $144.50 per month, according to an Appalachian Voices and Appalachian Citizens Law Center report. Adjusted for inflation, the 2023 figure should be $1,204.70; current law, though, allows for $738 per month.

Rebecca Shelton, director of policy at Appalachian Citizens Law Center in Whitesburg, Ky., supports the new silica dust rule — but with reservations.

“The Mine Safety Act says that, legally, any mining operation should not impair the health of the worker,” Shelton said. “Even if this rule goes forward, a lot of people are going to get sick and a lot of families are going to continue to be devastated by this illness, even though we know it’s preventable.

“And the gut punch is that we’re saying, ‘That’s OK,’ because we want to run more coal.”

New rule’s effect watched

MSHA’s new rule, the first for silica, restricts the dust exposure to 50 micrograms per cubic meter of air for a miner’s eight-hour shift. For reference, NASA said a typical droplet of rain weighs about 33,000 micrograms.

The proposal also includes exposure sampling and corrective actions such as penalties when exposure exceeds permissible limits, said Williamson of MSHA. This supplements MSHA inspections of U.S. mines that occur four times a year.

But some say the proposal lacks teeth.

“I think (the new rule) has the potential to do a lot of good, but as it’s written, I’m not sure it’s going to end this epidemic,” said Dr. Drew A. Harris, medical director of the black lung program at Stone Mountain Health Services in Virginia. “We can design a rule with good intentions, but if companies don’t follow those rules, it won’t help.

“I’m not convinced this is going to be the end of black lung.”

United Mine Workers of America, an 80,000-member union based in Virginia, feels stringent enforcement is essential.

“We have known for years that rising levels of silica in mine atmospheres was causing a dramatic increase in progressive massive fibrosis,” UMWA President Cecil E. Roberts said. “But this fight is far from over. This is the first step of many that will be required.

“We must ensure that mine operators follow the rule, the government enforces it and penalizes those who violate it.”

Enforcement manpower is an issue, Shelton said. Since 2013, MSHA’s staff numbers— or full-time equivalents — have dropped about 30%.

A group of 35 organizations, including some in Western Pennsylvania, pushed U.S. senators in May to increase MSHA funding in 2024 to $447 million, “particularly for staff to increase inspections at coal mines,” according to a letter obtained by the Tribune-Review.

Biden allotted $438 million in his 2024 budget to MSHA, a 13% increase from this year. Congress has not yet taken action. It must enact the spending package by Sept. 30 or risk a government shutdown.

“This administration has prioritized both miners’ safety and their health,” Williamson said. “Whatever resources Congress gives us, we’re going to make the most of it.”

Miners’ stories

Cecil Palmer toiled for 15 years at the #2 mine in Blacksville, W.Va., about 20 miles northwest of Morgantown and just a mile off the Pennsylvania border. A sign near the now-shuttered mine marks the location of the Mason-Dixon line.

In 2017, about five years before he retired, Palmer started having trouble breathing. One day, he barely could scale the 13 steps from the first floor of his house to his bedroom.

“By the time I got to the top of those steps, I thought I was gonna pass out — it was that bad,” said Palmer, 63, who lives on a four-acre property with rolling hills outside Fairview, W.Va. “I just couldn’t breathe. I felt like I was having a heart attack.”

He was diagnosed with black lung in 2017. He started receiving benefits about 18 months later.

His brother, John, worked at the same mine for decades. He also was diagnosed with black lung.

Today, John Palmer sleeps assisted by oxygen. He said he’s lucky if he gets four hours of sleep a night.

“In my heart, all those men I worked with for 35, 40 years, they all have black lung — and to the government, to the companies, we were just a number,” said John Palmer, 68, who lives in Monongah, W.Va., about 12 miles away from his brother.

“If they told me, ‘You should have a respirator,’ I’d wear one,” he added. “I know how it was at #2, and I tried to make it as best I could for my men. If my men were working, I was working. And I’m paying the fiddler now.”

Coal is in the brothers’ blood.

The Palmers’ dad, Cecil Sr., worked 11 years in West Virginia mines and developed emphysema, his sons said. He died suddenly in 1967 following a heart attack. His youngest son was just 8.

But with Cecil and John Palmer, the coal mining legacy ends.

“Coal mining’s been good to my family, I can’t lie,” said John Palmer, a former UMWA president for Local 1570. “But my boy never had to go into a coal mine — and I thank God.”

Cecil Palmer has two children and, with wife Barbara, three stepchildren.

“I wouldn’t let them go into those coal mines now,” he said. “No way in hell.”

Gary Hairston worked for more than 27 years in places like West Virginia’s Tommy Creek Mine or New River Coalfield, whose mining history dates to the 1870s.

Hairston, now president of the advocacy group National Black Lung Association, was diagnosed with the most severe form of black lung in 2002 — at age 48 — after battling pneumonia for a year.

“We said we wouldn’t get it. We said we couldn’t get it,” said Hairston, now 69. “You don’t think you can get it until you’ve got it.”

At a black lung clinic

Lynda Glagola is a respiratory therapist who moved to the Pittsburgh area 45 years ago.

In 2002, after treating miners at a Canonsburg Hospital black lung program, she founded Lungs at Work. Since then, the clinic has been based 21 miles outside of Downtown Pittsburgh in an unassuming Route 19 office park in Peters Township, Washington County.

“If you’re talking Pennsylvania, this is where the coal miners are,” she said.

Glagola has helped diagnosis thousands of black lung cases — she estimated about 500 or 600 each year. Lungs at Work has raised more than $30 million in black lung benefits since starting advocacy work in 2005.

Clinic doctor David Celko grew up in the Harwick section of Springdale Township, where in 1904 a mine blast killed 179 miners. It remains one of the worst mine tragedies in American history.

“My respect for miners has expanded exponentially as I’ve worked with these guys,” Celko said. “They’re very, very proud, hard-working, God-fearing men and women. And they tend to minimize any symptoms they have.”

M7, the public-relations agency for Consol Energy, did not return multiple calls and emails seeking comment. Officials from Patriot Coal Corp. — a now-bankrupt company that operated several mines in Appalachia, including one where Rankin worked — did not return calls seeking comment. Blackhawk Mining, which is based in Kentucky and reportedly acquired multiple Patriot Coal mines, also did not return calls.

Occupational hazard: Impaired breathing

Bethel Brock dropped out of high school at age 15 and started working alongside his father in the southwestern Virginia coal mines.

He worked 27 years for Westmoreland Coal Co. and was diagnosed with black lung in 2003. He started getting government benefits in 2015.

Today, at 83, Brock requires the constant use of oxygen.

“I pray a lot for my lungs to last,” he said. “I pray that I don’t have to smother someday.”

Willie Dodson, central Appalachian field coordinator for Appalachian Voices, said he has “never met a miner who is older than 40 who doesn’t have some degree of impaired breathing.”

“‘I was bulletproof till the day I could hardly walk out of the mine’ — I’ve heard that a lot,” Dodson said. “If these problems aren’t addressed, in 10, 20 years, what we’ll see is that who’s getting black lung is not going to change at all.”

Brock’s legs, weakened from a lack of oxygenated blood, keep him from tending a garden where he has planted vegetables for years.

Still, Brock keeps active.

When his mine closed in 1995, the miner, then 55, pursued a law degree at the University of Virginia. After graduating, he worked with a lawyer for eight years on coal miners’ black lung cases.

“We have an epidemic of black lung,” Brock said. “We have miners in their 30s waiting on lung transplants.”

He paused.

“I’ve been blessed.”