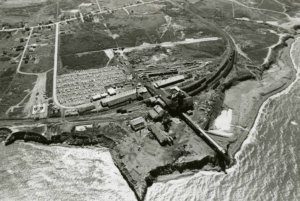

On February 24, 1979, fifteen Members of UMWA Local Union 4520 and a production foreman entered Cape Breton Development Corporation’s (DEVCO) Colliery No. 26 in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, Canada to begin their shift. The sixteen men, working the 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m. – midnight shift – descended into the mine and made their way five and a half miles to the No. 12 Southern Section of the mine. Referred to as the “Big Producer” by miners, the No. 26 Colliery was the leading coal producer in the area for many years and the No. 12 Southern Section, with its massive longwall, was key in establishing that reputation.

The Section was also unique because it was located nearly 2,500 feet below the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Work in the area appears to have progressed normally through the first five hours of the shift. Then at approximately 4:10 a.m., a miner on the  surface felt what appeared to be the concussion of an explosion in the mine. He immediately notified mine management and by 4:50 a.m., rescuers were arriving on the No. 12 Southern Section of the mine. Shortly thereafter, two doctors and a local priest entered the mine and were taken to the section.

surface felt what appeared to be the concussion of an explosion in the mine. He immediately notified mine management and by 4:50 a.m., rescuers were arriving on the No. 12 Southern Section of the mine. Shortly thereafter, two doctors and a local priest entered the mine and were taken to the section.

Rescue and Recovery

Despite the conditions the rescuers encountered as they entered the explosion area, they immediately began searching for members of the midnight shift crew. In short order, the sixteen miners were all located in the general area of the longwall section. Ten of the miners were killed almost immediately, succumbing to the effects of the explosion and noxious gases that filled the section after the blast. Six members of the crew, though seriously injured, were found alive. Two would later pass from their injuries while in the hospital.

The rescuers took immediate steps to secure the area and prepare the injured for transportation out of the mine. By 7:00 a.m., the six injured miners were on the surface and loaded into waiting ambulances for the short ride to Glace Bay Community Hospital. The initial plan was to stabilize the injured miners in Glace Bay and then fly them by helicopter to Victoria General  Hospital in Halifax. However, freezing rain and fog grounded air travel. These conditions forced the miners to be transported five hours overland by ambulance to Halifax.

Hospital in Halifax. However, freezing rain and fog grounded air travel. These conditions forced the miners to be transported five hours overland by ambulance to Halifax.

During this time, the rescue attempt at the No. 26 Colliery had transformed into a recovery effort. The bodies of the ten miners killed in the blast were carefully retrieved by the rescue team and loaded onto mantrips for transportation to the surface. By 12:00 p.m. on Saturday, February 24, 1979, all of the bodies had been removed from the mine and the official investigation into the worst mining disaster in Glace Bay, Canada since 1917 began.

Investigating the Explosion

The official report of the Commission of Inquiry: Explosion in the No. 26 Colliery, Glace Bay, Nova Scotia, February 24, 1979, determined the explosion was likely caused by” … sparking produced by the action of the shearers steel pick. . .into a high  ignition type of quarzitic sandstone. These sparks ignited a pocket of methane released from the coal during mining. The ensuing explosion was magnified when it ignited loose coal dust in the mine.” Despite the determination by the Commission of Inquiry (Commission) that the explosion involved float coal dust and over the objection of the miners that ventilation was inadequate and rock dusting was not sufficiently applied to the mine surfaces, the company was not held liable.

ignition type of quarzitic sandstone. These sparks ignited a pocket of methane released from the coal during mining. The ensuing explosion was magnified when it ignited loose coal dust in the mine.” Despite the determination by the Commission of Inquiry (Commission) that the explosion involved float coal dust and over the objection of the miners that ventilation was inadequate and rock dusting was not sufficiently applied to the mine surfaces, the company was not held liable.

In fact, the Commission specifically noted that, “Overall safety precautions were lax, allowing the explosion to occur, however, Devco was not solely responsible for this.” This determination made it possible for the Company to successfully defend itself against accusations of any wrongdoing.

“The explosion at the No. 26 Colliery was a tragedy, the likes of which Glace Bay had not experienced in over 70 years;’ said Secretary-Treasurer Allen. “It was, like mine disasters before it, an event that could have been prevented. Proper ventilation and adequate rock dust would have eliminated the ignition sources that permitted this explosion to occur, but like almost every other mine disaster we have seen, management’s first priority was production over safety. Then to have an official government body acknowledge these problems while absolving the company of responsibility, added to the grief and pain of those left behind. The fact that 40 years has passed does not lessen that heartache.”

body acknowledge these problems while absolving the company of responsibility, added to the grief and pain of those left behind. The fact that 40 years has passed does not lessen that heartache.”

Day of Mourning Called for Memorial Service

Wednesday, February 28, 2019, Ash Wednesday was declared a day of mourning for the Glace Bay area. The town was virtually shut down. Businesses and schools were closed and the local Glace Bay Miners’ Forum, an aging ice rink in the middle of town, was designated as the location for a memorial service.

The Forum built in 1939 saw 9,000 mourners pack into the arena that was designed to hold slightly over4,000 people. The service was the largest ever to be held at the facility and coincided with the funeral earlier that day of the last of the ten miners who perished in the mine on February 24, 1979.