Struggle & Win

Editor’s Note:

Keeping the UMWA’s history alive and relevant is a critical part of the union’s service to its members. If we do not know our history, then the harsh realities we overcame in the past cannot serve to guide us today. That is why we remember events like the Ludlow Massacre, the Farmington Mine Disaster, the Blair Mountain March, Davis Day and so many more.

Telling the incredible stories of the brave men and women who built our union is not just an exercise in research, it is an opportunity for us to learn how battles were won and what it takes to win them again.

Starting with this issue of the UMW Journal and continuing throughout 2024, we will recapture the last half century of our union’s victories and struggles. We’re calling the series Project 50: Struggle and Win.

UMWA’s 45th Consecutive Constitutional Convention

In September, 1968, the UMWA’s 45th Consecutive Constitutional Convention was taking place at the Denver Hilton. With nearly 2,000 delegates and 1,700 resolutions, the convention was iconic.

It was the first time in the UMWA’s history that a presidential candidate would address the membership. Hubert H. Humphrey, a staunch friend and supporter of working people, chose the UMWA convention to kick start his official battle to win over labor votes.

International Secretary-Treasurer Owens announced to the delegates that the International Union was in the best financial condition in history with assets of over $86 million.

Dr. Lorin E. Kerr, Assistant to the Executive Medical Officer of the UMWA Welfare and Retirement Funds and a recognized authority in coal miners’ dust diseases, presented an important paper on coal workers’ pneumoconiosis: The Road to a Dusty Death. The convention acted on a resolution that kicked off an all-out drive to bring a solution to the dust problems in American coal miners.

UMWA President Tony Boyle, in his closing remarks, said, “This union is going forward and forward and is going to be stronger and bigger than it was when I took office. I will have to use new techniques. I will have to use new ideas. And that is just exactly what I am going to do.”

In 1968, when Boyle spoke those words in front of his fiery delegation, no one could have known how true his words really were, nor the horrific set of circumstances that happened next.

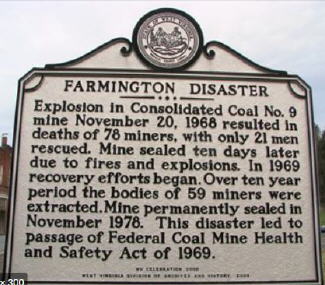

Farmington No. 9 Mine Explosion and the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act of 1969

It’s now been 55 years since 99 miners entered Consolidation Coal Company’s Farmington No. 9 Mine around midnight to begin their shift. At approximately 5:30 a.m. a massive explosion occurred. engulfing the miners inside. A series of explosions would occur thereafter. Twenty-one miners survived the initial blast and escaped. The other 78 miners were trapped inside. The lives of an entire community were forever changed.

The United States Bureau of Mines was immediately notified of the explosion. The first representative of the agency arrived at approximately 6:30 a.m. He issued two imminent danger orders for a mine explosion and a continuing mine fire. The orders restricted access to all underground areas of the mine except for necessary personnel approved by the parties involved in rescue and recovery efforts. Later that morning, UMWA mine rescue teams, state and federal mine inspectors, company personnel and representatives of the union arrived at the mine.

A day later, President Boyle arrived at the mine site and said to members of the press, “We have not given up hope. I came down here today not to give orders as to how the work should be conducted but more to make a showing here today on behalf of cooperation. This happens to be, in my judgement, as President of the United Mine Workers of America, one of the better companies to work with as far as cooperation and safety are concerned.”

Nothing was further from the truth, and those words didn’t sit well with the trapped miner’s families and members of the close-knit community. The small town of Farmington had never experienced what was bestowed upon them like a tornado.

News media from across the nation received word of the massive explosion and that 78 miners were still trapped underground. They flocked to the site, their cameras recording the smoke billowing from the mine

shafts and the grieving families.

It was the first time in history the effects of a coal mine explosion on family members and their community were televised across the country. They reported extensively on the disaster and without that coverage, Farmington may have been yet another unnoticed and forgotten mine explosion.

For nearly a week, all families could do was watch TV coverage, wait and pray for a miracle that never came. On November 29, the day after Thanksgiving, a meeting was held by officials who were working on the rescue and recovery operations. It was determined that all efforts to rescue trapped miners had been unsuccessful, air samples that were collected indicated the atmosphere could not support life and because of the fires still burning in the mine, further explosions were imminent.

Entrance into the mine from any location would not be possible and the only alternative would be to seal the mine. The news of sealing the mine was unbearable for family members to digest. The reality that their loved ones were never coming home had just begun to sink in.

After the mine was unsealed, ten days after the explosion, the bodies of 57 of the trapped miners were recovered. Nineteen never were, and they remain entombed in the mine. Widows, children and family members were grief-stricken but collectively decided they needed to do something so that others would not meet the same fate as their loved ones. They banded together and started demanding reform to anyone who would listen and to those who wouldn’t.

Congress Passes the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act

These grieving individuals, with the support of the UMWA, attended meetings in Washington, DC to testify at hearings on Capitol Hill. They lobbied members of Congress relentlessly.

Their efforts to better protect future miners came to fruition on December 30, 1969, with the signing of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act (Coal Act). It was a bittersweet victory. Their efforts would help save the lives of other miners and protect other families from suffering the horrors they had just experienced. But their loved ones still would never return home.

“November 20, 1968, was a day that brought great grief and pain to miners and their families,” said President Roberts. “The Farmington No. 9 tragedy and the horror of its aftermath was flashed on television screens

across the United States for all to see.

“For the first time, the American public saw what we in the coalfields always saw, which was that this industry was deadly, and the government did nothing about it,” Roberts said. “They witnessed the sorrow and pain of family members whose lives were devastated. It forced the nation to look at people who worked in the nation’s mines differently.

“In 2019, we held a special 50th year commemoration of the tragedy,” Roberts said. “What I said during that memorial service — and it will be true until the end of time — is that 50 years does not wash away the pain or fill the void of losing a family member. There is no amount of time that can heal those deep wounds.

“But we can take some solace in the fact that those brave miners did not die in vain. Because of their sacrifice and the determination of the family members, thousands of miners and their families have been spared a similar fate. Without their efforts, the Coal Act may have never been passed,” Roberts said.

President Roberts Begins His Coal Mining Career

On the heels of the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act being passed, a young man fresh back from Vietnam began his coal mining career in 1971, working various underground mining jobs at Carbon Fuel’s No. 31 mine in Winifrede, West Virginia. That young man was a sixth-generation coal miner from Cabin Creek, West Virginia, Cecil E. Roberts, Jr.

Roberts was no stranger to coal mining or the UMWA. His great uncle was Bill Blizzard, a legendary union organizer during the Mine Wars and the leader of the union forces at the Battle of Blair Mountain. His father was a stalwart UMWA member.

He rose through the union’s hierarchy relatively quickly. He was active in his local union and District 17. In 1977, he was elected Vice President of District 17. Five years later he ran as the International Vice President candidate on the ‘Why Not the Best?’ slate with Richard L. Trumka and John Banovic. On November 9, 1982, the Trumka, Roberts, Banovic slate was elected by a 2-to-1 margin.

“There are plenty of books, UMW Journals and newspaper clippings about our history, especially the Mine Wars, the John L. Lewis era and Mother Jones,” Roberts said. “But it is up to us to make sure we secure our place in the history books for what we have accomplished in the last 50 years, and that’s what Project 50 is all about.

“Thirty, forty or fifty years from now we don’t want anyone to forget that the Coal Act was passed or how we won the strike against the Pittston Coal Company,” Roberts said. “We don’t want people to forget that our retirees took on bankruptcy judges, Wall Street raiders and walked the halls of Congress for years to get legislation passed for pensions and healthcare. No one thought we would win, but we did.

“No one else is going to tell our story for us. It’s up to us to preserve it, share it and educate others about that history, good and bad,” Roberts said.

UMWA Election Year: Yablonski Murders and How the Expulsion of District 50 Played a Role

Tony Boyle was reelected to office on December 9, 1969, along with George Titler and John Owens. Boyle’s opponent for president, Joseph “Jock” Yablonski, filed charges disputing the election results as fraudulent. On New Year’s Eve, just a few weeks after the election, “Jock” Yablonski, his wife Margaret and daughter Charlotte were murdered in their Pennsylvania home. Jock’s son, Ken, went to check on his father in Clarksville, Pennsylvania and found the grisly scene. His mother, father and sister were killed in their bedrooms. Tires to their cars had been slashed and the phone lines to the house had been cut. Early in the investigation, law enforcement believed more than one person was involved in the triple homicide. Investigators ultimately uncovered a conspiracy that stretched to Boyle himself. The criminal warrant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania stated that Boyle said to Albert Pass, president of District 19 and loyalist to Boyle, “Yablonski ought to be killed or done away with.” Shortly after, District 19 received $20,000 for a research fund from the union. Checks were cut to retirees who cashed them and gave the money to Pass who used the money as payment for murder of Yablonski and his family members.

Boyle had become cozy with mine owners, as evidenced by his late arrival at the Farmington No. 9 mine disaster and praise of the company’s safety record. Boyle had removed Yablonski from his position as District 5 president in 1965. He had 100,000 extra ballots printed to be stuffed in the ballot box. Two weeks before the ballots were to be counted, Pass told Boyle the vote totals from District 19; he had won the district and the election.

In April, 1970, Miners for Democracy was formed to continue reform efforts championed by Yablonski and to have the 1969 election invalidated. A judge eventually threw out the election results and set new elections in 1972. Boyle was challenged and lost to Arnold Miller. Boyle was ultimately arrested and convicted of conspiracy in the Yablonski murders. He was one of nine people who went to prison for the killings. Miller was a miner from West Virginia and struggled with Black Lung. He became a strong advocate for miners with the disease and led efforts in Washington, DC to persuade Congress to strengthen dust regulations in mines, culminating with an amended Coal Act in 1977 that created the Mine Safety and Health Administration and set respirable dust limits. Miller resigned on November 16, 1979 due to poor health relating to black lung. He passed away in July, 1985.

Sam Church, Jr., New UMWA President

Upon the resignation of President Miller, Vice President Sam Church, Jr., assumed the leadership on November 16, 1979, per the union’s constitution. Church was the son of a disabled coal miner and worked in the mines as an electrician and mechanic for Clinchfield Coal Company.

In 1981, Church led the union on a two-month nationwide coal strike. After a tentative agreement was rejected by the membership, he negotiated a new contract that included improvements in benefits. Staring at reelection in 1982, Church set his campaign in motion. Challenging Church and his slate was the ‘Why Not The Best?’ slate of Trumka, Roberts and Banovic. It was a hard fought and bitter campaign. Church lost the election but remained active in the union, going back to work in the mines and serving as coordinator for Virginia’s COMPAC. Church passed away on July 14, 2009 after complications from surgery. “Sam was a good friend and a good union man,” Roberts said. “He never stopped fighting to restore the right to organize, for better health care for working families and for safety in the workplace. Even though we ran against each other in the 1982 election, we were always able to see eye to eye when it came to the best interests of the UMWA. We lost a great friend and labor leader when we lost Sam Church,” Roberts said.